News & Commentary

Aug 13, 2018

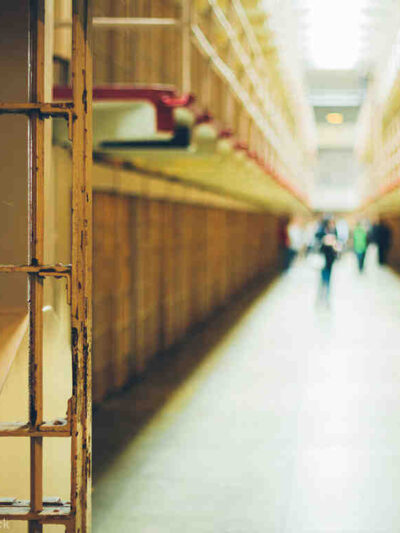

Imprisoned in Isolation

In a recent study, the ACLU-VA asks Governor Ralph Northam to sharply limit the use of solitary confinement. The ACLU report deems the practice is 'overused' in Virginia. The ACLU said reforms put in place by the state since 2011 are a “step forward” in reducing its use but don’t go far enough.

May 10, 2018

Solitary Confinement Degrades and Dehumanizes Real People in Virginia Every Hour of Every Day

The findings of the ACLU-VA's latest report, Silent Injustice: Solitary Confinement in Virginia, are at once startling and cursory to the real inhumanities people in solitary confinement face.

By Mateo Gasparotto

Apr 24, 2018

We Can’t End Mass Incarceration Without Ending Money Bail

Even though you are presumed innocent in the eyes of the law, if you can’t afford cash bail, you will end up in jail for weeks, months, or, in some cases, years as you wait for your day in court.

Feb 19, 2018

These 'criminal justice' proposals can't truly be called 'reforms'

Lawmakers, opinion leaders, and some in the media have characterized several proposals making their way through the Virginia legislature this year as welcome “criminal justice reform.” They are anything but.

Feb 15, 2018

Linking Restitution with Probation Treats People Differently Based on Ability to Pay

Today, the ACLU of Virginia sent a letter to Secretary of Public Safety Brian Moran to address some major concerns that we have regarding the so-called bipartisan compromise to raise the felony larceny threshold from $200 (the lowest in the nation) to $500 while putting those convicted on probabtion until they pay all of their restitutions.

Nov 27, 2017

Cuccinelli and Gastañaga: Making Change Virginians Can Agree On

We will continue to work against each other on issues on which we don’t and can’t agree and will seek to bring others to those causes. We know others will do the same.

Jul 06, 2017

Seven Questions For Virginia’s Attorney General Candidates

As Virginia voters prepare for the fall elections for our three statewide offices, it’s important to focus some attention on the race for the job of attorney general. Here are some questions to ask that will help you decide whom to hire as Virginia’s lawyer when you enter the voting booth on Nov. 7.

Mar 15, 2017

WATCH: Our Executive Director Claire Guthrie Gastañaga's Remarks in response to U.S Attorney General Jeff Sessions' Visit to Richmond

On Wednesday, March 15, U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions met with local, state, and federal law enforcement representatives in Richmond on violent crime and public safety. Our Executive Director Claire Guthrie Gastañaga addressed a crowd of protesters, who showed up to oppose the Trump administration's unconstitutional policies, in front of the SunTrust Center, where the meeting took place. You can watch her address here:

Stay Informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU’s privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU’s privacy statement.