By Amanda Nelson, executive editor, Book Riot

As the executive editor of the country’s largest book site, I’ve noticed that most readers think book banning is a relic of now-extinct oppressive governments from history. They imagine piles of books burning in Germany, or maybe in Footloose. It’s not something we have to deal with now, people think. And while we do still have religious-based book burnings in the U.S., book banning in 2020 looks more like challenges and book removals in public libraries, school curriculums, and prisons. This is censorship which affects some of the most vulnerable members of our society: children and people who are incarcerated.

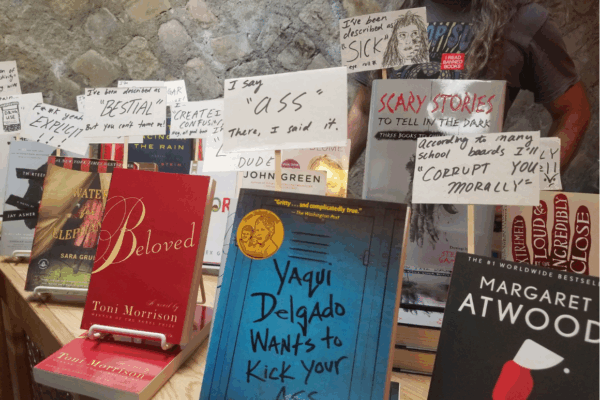

The American Library Association releases a list every year of the most banned and challenged books in libraries and schools, and the books most commonly removed are by or about LGBTQ people, or by or about people of color. The reasons people give for challenging these books range from “encourages kids to clear their browser history” to “anti-cop sentiments.” Prisons across several states have quietly begun banning book donations entirely, and increasing the amount of titles banned from prisons; in fact, taken as a whole, restrictions on reading in prisons constitute the country’s largest organized book ban. The most frequently banned books in prisons are those about race and civil rights, despite the fact (or perhaps because of the fact) that Black and Hispanic prisoners account for 56% of the prison population in the United States, a percentage that vastly outstrips the percentage of Black and Hispanic adults in the population of the country.

While we don’t often see piles of books being burned on the nightly news these days, the motives for America’s more modern and mannered book bannings are the same: keeping vital books out of the hands of people who would use them to learn their own power, and learn how to exercise it.

Books are banned from prisons when they are interpreted by the prison administration to have the potential “to disrupt a prison’s social order,” according to PEN America, and it’s easy to see when looking at the lists of books banned from schools and libraries that much the same is happening there. Essential stories and information are being kept from people who need it in the name of maintaining their “safety.” Incarcerated people are denied books that would help them advocate for themselves. Children are denied books that would allow them to see themselves represented in stories, that would encourage them to use their voices. While we don’t often see piles of books being burned on the nightly news these days, the motives for America’s more modern and mannered book bannings are the same: keeping vital books out of the hands of people who would use them to learn their own power, and learn how to exercise it.

It is perhaps preaching to the choir to remind an ACLU audience that literary freedom and unfettered access to information is essential. In addition to your donations to the ACLU, I would encourage you to participate in PEN America’s efforts to end book banning in prisons (PEN America is a wonderful literary organization dedicated to free expression across the world, and that supports persecuted writers). Also, please pay attention to what is happening in your own community’s schools and public libraries. The removal of a book from a school’s library or curriculum is often debated at school board meetings – attend them and voice your support for the freedom to read in our schools. Recognize the removal of books by LGBTQ authors and people of color for what it is – homophobia and racism – and call it out in those meetings. Encourage local parents who object to a book’s inclusion in a library or curriculum to talk to their children openly about the topics in the books, instead of trying to remove it and thereby dictate to the community what books are available.

And of course, head over to your public library and check out a few banned books!